The world is aging.

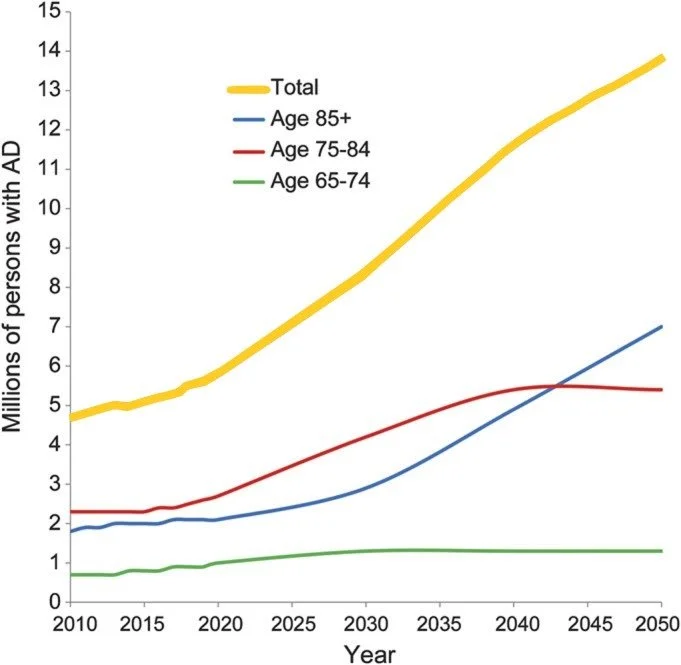

In about ten years, the United States will have more old (65+) people than children, and the global elderly population will double current numbers by 2050. Advanced age is the greatest risk factor for most severe disease outcomes in developed countries, including neurodegeneration, cancer, and COVID-19. The global incidence of Alzheimer’s disease dementia is expected to triple by 2050 (Figure 1), and similar projections for other symptoms and diseases of aging add up to a terrifying healthcare burden: two thirds of the ballooning 65+ population suffer from two or more chronic diseases at the time of writing, and patients with multiple diseases account for up to 78 percent of primary care consultations. Eliminating these age-related diseases is essential for ensuring a healthier and more capable society moving forward.

Disease-focused initiatives have shown that though biology is complicated, concerted human effort does allow us to influence how it affects us. For example, the decades-long national push to advance cancer research, which has stretched from the National Cancer Act (1971) to the Cancer Moonshot (2009), has doubled five-year cancer survival rates.

While such improvements are certainly meaningful, even focused initiatives to tackle specific diseases take time to impact the population (Figure 2). Further, multimorbidity—the presence of multiple diseases or conditions—is so prevalent at advanced age that curing a common disease like cancer would not dramatically reduce the population’s overall disease burden. We intuitively know, and can observe from the incidence of major diseases with age (Figure 3), that young people don’t typically get heart attacks, dementia, or cancer, while older people get them all—and often more than one at a time. The prevalence of multimorbidity in older people suggests that the risks of age-related diseases are not independent. This interdependence of age-related diseases could be due to one or more shared drivers of disease. As such, tackling disease targets on a “one-by-one” basis may not be an optimal strategy for significantly addressing the growing healthcare burden within the next few decades.

A “one-by-one” approach is typical of standard randomized, double-blind clinical trials to identify new disease treatments. These clinical trials assume that the most efficient path to new disease treatments is independent testing of drugs against each disease. Though the repurposing of drugs to target alternative or additional indications does occur, the initial clinical trials generally collect insufficient data for identifying new drug applications. The recent FDA endorsement of “Master Protocols” to study drugs’ effects on multiple diseases highlights the limitations of conducting individual clinical trials for each drug-disease pair. If the major diseases of our generation are not independent, the status quo clinical trial methodology is analogous to solving a jigsaw puzzle by picking up a piece, testing whether it fits, and throwing it back into the pile if it doesn’t. We are likely to solve the jigsaw puzzle eventually, but it will take far longer than it needs to.

The MCARD strategy envisions an alternative approach to identifying therapeutics: mobilizing every United States clinical trial to find therapies that are effective against multiple age-related diseases. Achieving this goal will involve including in every clinical trial non-invasive biomarkers that measure a given drug’s effects on the biological mechanisms coupling the occurrence of multiple age-related diseases. We call these biomarkers “mechanistic” biomarkers: they measure the biology driving disease, rather than biology that is caused by or correlated with disease. (High) blood pressure and (high) cholesterol are examples of successful mechanistic biomarkers that predict the incidence of multiple cardiovascular disease, kidney failure, and retinal disease. Because these biomarkers measure the biology that drives disease outcomes, they have evolved into surrogate endpoints: changing the biomarkers demonstrably affects disease outcomes.

Figure 1. Projections of the number of people who will suffer from Alzheimer’s disease dementia in the United States by 2050. Over half of Alzheimer’s disease dementia sufferers in 2050 will be aged 85 years or older. Figure adapted from Hebert et al. 2013.

Figure 2. United States cancer death rates decreased by 27 percent between 1999 and 2019. Figure recreated using data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Figure 3. The incidence of major diseases and symptoms such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s disease dementia and diabetes increases with age, often dramatically. Data aggregated from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2014), the American Heart Association (2015), the Alzheimer’s Association (2017), and the International Diabetes Federation (2013).

The past two decades of geroscience research have demonstrated that we can target with interventions the biological mechanisms that drive aging.

These mechanisms, which include the accumulation of dysfunctional senescent cells, immune system weakening, and a decline in cells’ capacity to remove damaged components, among other things, are promising leads for mechanistic biomarker development. Because the number of such biological mechanisms is much smaller than the number of diseases that could afflict an individual, researchers could measure a drug’s impact on each mechanism using small fluid samples collected during existing clinical trials, thus eliminating the need to measure clinical endpoints for every possible disease.

In summary, MCARD proposes to address the impending epidemic of age-related multimorbidity in the United States and worldwide via a novel approach to clinical trials: by mobilizing every clinical trial to evaluate a therapy’s potential to treat multiple diseases at once, and doing so by measuring during every clinical trial a set of biological mechanisms that couple multiple age-related diseases. To enable this outcome, MCARD aims to 1) Facilitate the coalitions necessary for developing clinical-grade, minimally invasive biomarkers for interpretable mechanisms of age-related decline; 2) Spearhead the initial clinical trials to validate these mechanistic biomarkers as surrogate endpoints; and 3) Orchestrate the necessary institutional infrastructure and political mandate to accomplish MCARD’s core goal.